A new study provides the "strongest evidence yet" of salty liquid water that flows on modern-day Mars, researchers said on Monday in a groundbreaking discovery that holds implications for future expeditions to the Red Planet.

"Our quest on Mars has been to 'follow the water' in our search for life in the universe, and now we have convincing science that validates what we've long suspected," said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator at NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C. "This is a significant development, as it appears to confirm that water -- albeit briny -- is flowing today on the surface of Mars."

"The discovery we're going to talk about today really is most exciting because it suggests that it would be possible for there to be life today on Mars," Grunsfeld said.

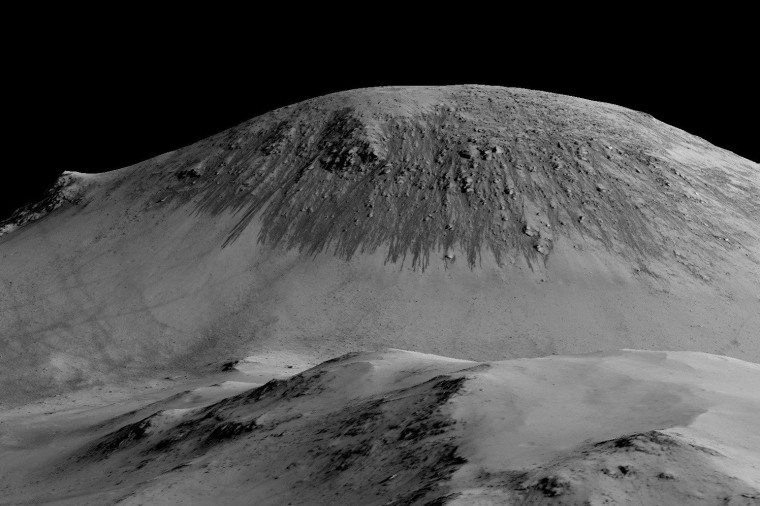

Researchers from Georgia Tech led by doctoral candidate Lujendra Ojha used science tools aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter -- which has been circling Earth's neighbor since 2006 -- to investigate streaks (or "recurring slope lineae") that appear across parts of the planet during the warm seasons and disappear when it gets colder.

The evidence suggests that the streaks are formed by salty water that comes and goes with the Martian seasons, the researchers found. The study was conducted with researchers from NASA Ames Research Center, Johns Hopkins' Applied Physics Laboratory, the University of Arizona, the Southwest Research Institute and Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique de Nantes, and was published on Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"Something is hydrating these salts, and it appears to be these streaks that come and go with the seasons," Ojha said in a statement. "This means the water on Mars is briny, rather than pure. It makes sense because salts lower the freezing point of water. Even if RSL are slightly underground, where it's even colder than the surface temperature, the salts would keep the water in a liquid form and allow it to creep down Martian slopes."

The team used the orbiter's Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer, which detects and identifies minerals on the planet's surface.

Where this water could be coming from, researchers say they don't know yet.

"The origin of water forming the RSL is not understood," they wrote in their study. "Water could form by the surface/subsurface melting of ice, but the presence of near-surface ice at equatorial latitudes is highly unlikely."

Using tools from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and other probes, scientists have been poring over data from Mars for years looking for evidence that water might be flowing on the planet's surface today. Experiments conducted by the Curiosity rover mission reported in 2013 that an area called Yellowknife Bay might once have been a huge 30-mile-long lake that could have made a nice home for microbes -- but that was probably something like 3.6 billion years ago.

Earlier that same year, the team behind the Opportunity rover found evidence that the planet had once had non-acidic water, the kind "you can drink."

Other NASA findings have indicated that a Martian ocean might once have had more water than the Arctic Ocean.

This article originally appeared on NBCNews.com.